Mimetic desire, PsyOps, and rock-n-roll in the GDR

How Rene Girard might have helped the West take down communism

With Germany’s reunification, we were lucky to leave behind the stale, comatose mindset of government control in the East German Democratic Republic, GDR. People were governed by apparatchiks who contributed little but omnipresent, mediocre rulership and technocrats who lined their own meager pockets.

Despite or because of this government control, there was art, storytelling, and imagination, like light looming through concrete cracks.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Under the loving supervision of space titans

Sunlight broke through the classroom window, slanted silver stripes of sparkling dust. The scent of spring awakened my senses. The sun’s warmth lightly brushed my elbow as I dutifully wrote in my school diary.

The back of our classroom featured photos of the first astronauts — we called them cosmonauts in those years: Gagarin and Tereshkova. Our energetic teacher must have decided to use cosmonauts instead of the portraits of Lenin, Marx, and Honecker.

In its terrarium at the back of the class, our little tortoise watched those titans of space as it chewed on the grass leaves we picked from outside. We had just come in from gardening class, planting crocuses and delivering breakfast for our tortoise.

The state took care of our breakfast. A boy and a girl dressed in imposing blue shirts with a yellow emblem from the upper echelons of grade 8 brought us our daily chocolate milk bottles. We looked up to them as superheroes—we had no Marvel comics back then.

What we had was the ABC Newspaper. It was a country-wide newspaper for elementary school kids with riddles, crosswords, stories, and more. We loved the articles. Another read was Mosaik, a comic series about three children exploring the world. We couldn’t ignore these comic books describing travels to ancient India and Japan. One might think that the censor-approved writers of those comics themselves imagined a more spirited existence in a country far, far away.

Concrete & dirt — a crucible for our imagination

For most of us, our childhood was shielded from reality and loving. We didn’t know there was a wall somewhere in Berlin that we could not cross. We did not know what blue jeans were; we had never heard of Coca-Cola, Mickey Mouse, or pizza. We did not know the unspoken names of dissidents who withered away in prison cubicles.

As children, we were in the moment. Smartphones only existed in science fiction comics and movies. We lived in a newly built neighborhood of brutalist concrete boxes, which was affluent in those days. Unlike older buildings with outside communal facilities, my parents had been assigned a two-bedroom flat with a bathroom inside. Next to our building was my school, and next to my school was a colossal dirt hill left there during construction.

The dirt hill was our playground. We rode our child-sized folding bicycles up and down the little dirt moguls surrounding the enormous hill. We created games from our imagination; inspired by Karl May’s Winnetou stories, we organized ourselves in tribes at war with one another. We built treehouse bases to plan our raids on the rival tribes. As I said, smartphones were not a thing back then.

The greyer our environment, the more vibrantly we dreamt. I vividly remember looking up at my mother at a train station; we traveled to the mountains for a hike. A dusty diesel locomotive passed by, engulfing the platform in an acrid, metallic smell that tingled the tongue with the taste of silver. My physicist mother looked at the wreck of a train dragging itself into the distance and said:

“One day, trains will levitate, and we will travel at extreme speeds. Rail networks will be replaced with a magnetic carpet enabling trains to levitate and accelerate to speeds so fast; you would not see them pass within a blink of an eye.”

Maglev trains came into production about one or two decades later.

In the GDR, no matter where you looked, you would see people compensating for material scarcity with imagination and resourcefulness. No fashionable clothes in the stores? Sew your own. Tired of listening to that Beatles LP for the hundredth time? Form a band and find your voice before censorship finds it. The cookie-cutter furniture from the store looks like the saddest version of mid-century modern.

Become your carpenter. Want a car for your children? Order it right after they were born; the waiting list was 15–20 years.

We had the basics but little else. People were inventive in a country of essential but few supplies. In our concrete crucible, imagination filled gaps in every walk of life.

The growing embrace of the state

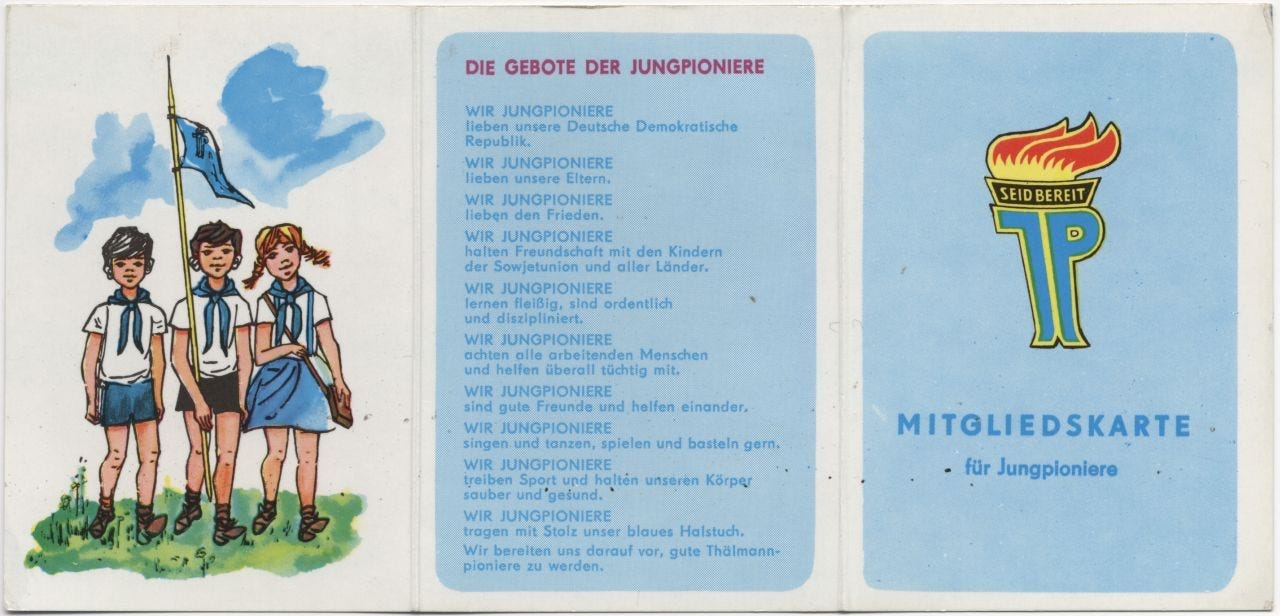

Early on, we were required to become Young Pioneers, a youth party organization for elementary school children. As proof of our affiliation, we carried a membership card. This card prescribed the ‘commandments of the youth pioneers’: “We love our parents,” We love peace,” We foster a friendship with the children of the Soviet Union and all countries,” We learn eagerly, are orderly, and disciplined,” “We love our country.”, etc.

A political membership card — at primary school shows how kooky the ideology was. It will not have gone unnoticed to the reader that the political commandments on the card are similar to religious ones.

“If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.” — Voltaire.

As pioneers, we were required to participate in rituals. Marching across the schoolyard in our white shirts and blue scarves before about fifty ‘Doves of Peace’ were released was a familiar spectacle for our parents.

In theory, socialism was about realism and materialism. Yet, it always felt like we replaced religion with contrary idolatry, the religion of the state. As children, we believed the future would be better — despite that carelessly abandoned dirt hill that outgrew the roof of our school building.

An ocean of white dots on the silver screen

As artificial as the GDR was, its collapse was inevitable. One evening, on our tiny black-and-white TV, we saw the silhouette of the Brandenburg Gate surrounded by waves of white dots of light—an ocean of people assembled around it. The low picture quality allowed us to fill the fuzzy image with what we imagined it must be like to be in the crowd.

As a child, I did not comprehend what I was seeing. My friend, who was four years older than me, explained it all as we rode our bicycles through the moonscape of our dirt hill. “Look, it will be like this: East Germany will become West Germany, and West Germany will become East Germany.” Those words stuck with me. I could not fathom why West Germany would want to become East Germany.

It took my parents several attempts to explain that we would not switch sides but form a united Germany. As we discussed current affairs at the dinner table, everyone tried to imagine a bright future.

PsyOps — Hacking FOMO to topple tyrants

No one likes to live in a scarcity of space, yet plenty do not mind living in East Germany. Why did socialism fall? There are theories astute historians can explain. It will have to do with repression, rise against tyranny, state economics, restricted travel, and more. One reason that stuck with me was how the West used the people’s imagination.

We hardly knew life outside the concrete crucible. We were exposed to a few Western censor-approved movies like E.T. or the BMX Bandits. We watched the bicycle scenes in these movies, then met near that dirt hill to recreate stunts on our tiny folding bikes. Even though we never managed to ride our bicycle past the moon, we imagined we could.

For people to want something, they need a model of what to like. Rene Girard called this concept ‘mimetic desire.’ The Cold War was a clash of pictures, a war for what to desire. In his book, Thomas Rid masterfully highlights the types of influence the US and the Eastern bloc exerted on each other. The West might have called it ‘PsyOps’; the Soviets called it ‘Active Measures.’

Thomas Rid explains how Western powers influenced the population to want more than the socialist world could offer. In the late 50s, in Project LCCassock, the CIA distributed magazines and newspapers across the GDR. This included the fake gossip magazine *Klatsch*, which planted disinformation and conspiracy theories about communist leaders. *Schlagzeug* was a jazz magazine that music-starved people in the Eastern block read. “Along with astrology, we consider [jazz] one of the most potent psychological forces available to the West for an attack on Moscow Communism,”says a CIA operative in Rid’s book.

Fast-forward to the neon-colored 1980s, when Western influence was amplified by its immense media apparatus. Families close to the Western border could receive Western media via aerials. It was dangerously illegal, but few people could resist. An antenna pointing to the West was a clue of someone heedlessly losing themselves on 21 Jump Street, Beverly Hills 90210, or the bridge of Battleship Galactica. Zealous communist neighbors would patrol and observe the direction of aerials on the roof; any wrongdoing was diligently reported to the state.

There is speculation that the CIA arranged rock anthems. Wind of Change, a podcast by Pineapple Street Studios, explores the events after the fall of the Berlin Wall that led to the Scorpions’ earworm of said name.

In the Eastern bloc, socialist rulers had limited options for defining their desires. The state created a library of movies that displayed class struggles, such as Grimm’s stories, Hans Christian Andersen’s Snow Queen, and folk tales such as Krabat. Created in the 1970s and 80s, these movies are still broadcast today.

As long as art did not question socialist rule or underscore the shortcomings of the ‘chaotic’ capitalist West, it was funded and supported. Socialist art was supplemented with impossible-to-reach ideals and narratives; Yuri Gagarin, for instance, was an everpresent ‘hero of the working class.’

People sensed the difference between ideal and reality and craved self-fulfillment. Socialist censors could not keep pace with flourishing Western media. The Rolling Stones and blue jeans became essential distractions for the East German population. Western leaders knew injecting contradicting desires and narratives into society could topple tyranny.

Sculpting new meaning

After Germany's reunification, a massive influx of Hollywood movies taught us what to expect from our new world. We saw lawyers, karate fighters, robot cars, and monumental mansions. In Red Heat, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, even American and Russian police officers were friends. That was then, and note the contrast between the US and Russia today, 25 years later.

For a few, the mansion and the hot job panned out. For most, Germany's reunification brought about an economic collapse, followed by decades of rebuilding, career disruption, and mass unemployment.

The children who experienced the collapse of socialism now form a middle-aged stratum in society. To this day, this group will be influenced by the collective trauma of dictatorship and by the confusion during its aftermath. Ostkinder 80/82, a podcast, and Ostkind, a novel, are written by authors shaped by the GDR's fall.

When I look back, I wish there was a simple ending to this story. In the stale, concrete world of the GDR, the imagination of a better future set the perfect conditions for political upheaval. However, it uprooted an entire generation, many still searching for new meaning.